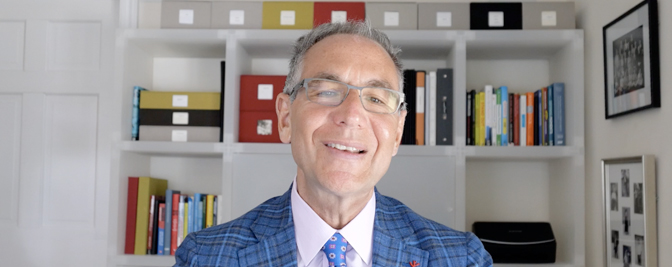

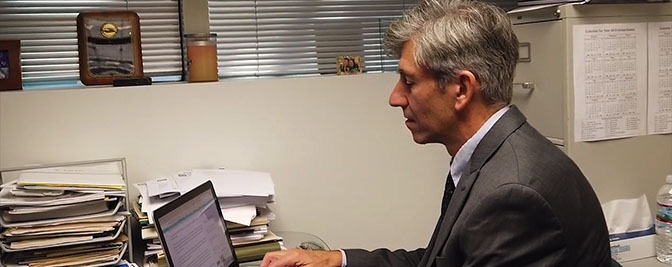

Ronald H. Weich, Prominent Legal Authority, Named Dean of Seton Hall School of Law

Following a nationwide search, the Office of the Provost has announced the appointment

of seasoned attorney and law school administrator, Ronald H. Weich, J.D., as the next

dean of Seton Hall School of Law. Read more >>

Experiential Learning Bridges Opportunities for School of Law and Undergraduate Students

Seton Hall University School of Law will deliver its Denis F. McLaughlin Advanced

Trial Advocacy Workshop this coming January 2024. Read more >>

Seton Hall University Law School Sports Law Symposium Highlights a Year of Unprecedented

Investment in Sports

Seton Hall University Law School held its Fourth Annual Sports Law Symposium on Wednesday,

November 8, 2023, centered around the theme “Money in Sports,” and the evolving landscape

of investment in sports betting, sports media, and teams and leagues. Read more >>

Professor Gaia Bernstein Publishes Op-Ed in The Hill "California is right: Addictive

tech design is not free speech"

Professor Gaia Bernstein recently had her Op-Ed "California is right: Addictive tech

design is not free speech" published in the Hill. Read more.

Law Professor Doron Dorfman Receives Employment Law Rising Scholar Award

Seton Hall Law Professor Doron Dorfman received the Michael J. Zimmer Memorial Award

for a rising scholar who has made a significant contribution to the field of work

law. Read more.

Seton Hall Law Community Members Named to American Association of Law Schools 2023

Pro Bono Honor Roll

In 2023, Seton Hall Law School named three members of our community to the Pro Bono

Honor Role to recognize the tremendous contributions they have made to both the University

and the community. Read more.

Seton Hall Law Welcomes William Coppola, as the new Distinguished Practitioner in

Residence for the Gibbons Institute for Law, Science and Technology

Mr. William Coppola joins Seton Hall Law as the Gibbon’s Institute for Law, Science

and Technology Distinguished Practitioner in Residence. Seton Hall Law enthusiastically

welcomes Bill and his extensive experience in patent, intellectual property, and transaction

matters to enrich the student experience and intellectual property legal learning

community. Read more.

Law on Film, a Podcast Created and Hosted by Seton Hall Law Professor Jonathan Hafetz

Seton Hall Law Professor Jonathan Hafetz created and hosts the podcast Law on Film.

Law on Film explores the rich connections between law and film. Law is critical to

many films, even to those that are not obviously about the legal world. Read more.

Professor Sara Gras, Host and Content creator for Season 1 of the New Podcast, "Hearsay

from the Sidelines"

Professor Sara Gras is hosting and producing Season 1 of the new podcast, “Hearsay

from the Sidelines” for Culture in Sports. Read more.

Forbes Names Seton Hall Law School Graduate Program a Best Online Master's in Legal

Studies of 2023

Editors compiled data in five categories: credibility, affordability, student outcomes,

student experience, and application process. The online MLS at Seton Hall was selected

in part because of the student experience: most students enroll part-time, taking

one course at a time and graduating within two years. Read more.

Seton Hall Law's Latin American Law Students Association (LALSA) received the Hispanic

National Bar Association's (HNBA) Law Student Organization of the Year Award

On September 7, 2023 Seton Hall Law’s Latin American Law Students Association (LALSA)

received the Hispanic National Bar Association’s (HNBA) “Vision in Action” Law Student

Organization of the Year Award. Accepting the award at the HNBA Annual Convention

were Co-Presidents, Taylor Lugo-Maestas ’24 and Justin Perez ’24, along with Natalia

Sifuentes ’24, LALSA’s HNBA representative. Read more.

Award-Winning Law School Leadership Fellows Program Welcomes Rehan Staton, Esq.

Last week marked the start of the new academic year for the award-winning Leadership

Fellows Program, comprised of a selective cadre of Seton Hall Law students with demonstrated

leadership ability. Read more.

A Demographic and Legal Profile of January 6 Prosecutions

The Center for Policy & Research at Seton Hall University has released a report, "The

January 6 Insurrectionists: Who They Are and What They Did," which presents demographic

data and provides a detailed examination of the disposition and charges brought against

the 716 persons prosecuted in the first year after the storming of the Capitol. Read more.

Seton Hall Law Professor Awarded Prestigious Fulbright Scholarship

Professor David Opderbeck has received a Fulbright U.S. Scholar Program award for

the 2023-2024 academic year from the U.S. Department of State and the Fulbright Foreign

Scholarship Board. Professor David Opderbeck will examine regional differences in

AI regulations and their impact on privacy and security. Read more.

Center for Social Justice Recognized Students for Outstanding Work and Commitment

At the annual awards ceremony for graduating students, held on May 24, 2023, the Center

for Social Justice (CSJ) recognized students for outstanding work and commitment in

each of its legal clinics. The CSJ also recognized one team of students overall for

their exemplary clinic work and one student overall for their excellence in the service

of our clients. Congratulations to the award recipients! Read more.

Law Professor Publishes Article in New England Journal of Medicine on Long Covid Work

Accommodations

Seton Hall Law Professor Doron Dorfman and Professor Zackary Berger, M.D., of Johns

Hopkins School of Medicine, have published "Approving Workplace Accommodations for

Patients with Long Covid — Advice for Clinicians" in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Read more.

Highlights from Seton Hall Law School Abroad: European Union Business Law Travels

to Brussels and Luxembourg

Professor Tracy Kaye guided law students from her EU Business Law course on a trip

through the EU Institutions of Brussels and Luxembourg over Spring break in early

March 2023. The trip was designed with the vision to provide an immersive learning

experience and cultural exchange with the EU to enrich the U.S. legal perspective

with an appreciation of the inner workings of European Institutions and their legal

system. Read more.

Seton Hall Law Achieves Best Overall U.S. News Ranking in Its History

The Law School jumped 17 places to 56th overall and was ranked 12th best Part-Time

program and 11th best Health Care Law program in the nation. Read more.

An Interview with Gaia Bernstein, author of the celebrated book UNWIRED

Seton Hall Law Professor Gaia Bernstein's new book, Unwired: Gaining Control over

Addictive Technologies (Cambridge Press) has been generating buzz since its March

2023 release. Not only has the publication prompted news outlets, such as the Boston

Globe and Bloomberg, to interview Bernstein about her book, well-known magazines including

Wired, Time Magazine, and Fast Company have devoted significant space to the content

in the book. Read more.

Justice Served by Law School’s Exoneration Project: Another Freed!

Spearheaded by Lesley Risinger J.D.’03, the director of the Last Resort Exoneration

Project at Seton Hall Law, and Project co-founder, Professor Emeritus Michael Risinger,

the State of New York has vacated the conviction of Sheldon Thomas and released him

from custody. Arrested when he was 17, Thomas spent more than 18 years in prison under

a wrongful conviction for murder. Read more.

Commitment to Social Change: Center for Social Justice Scholars Program (2022-23)

Each year, the Center for Social Justice selects second-year students to serve as

CSJ Scholars. Selected students include Fatima M. Abughannam ’24, Shaindy Black ‘25,

Eric Gallant ’24, Myron Minn-Thu-Aye ’25, and Jamie Mitrovic ‘24. Learn more about the program and selected students.

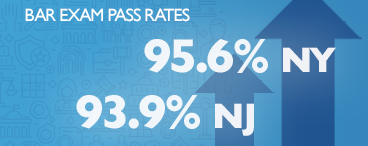

Seton Hall Law Ranks 31st in Nation for First Time Bar Passage Rate

Seton Hall University School of Law ranked 31st in the nation for first-time bar passage

rate. According to statistics released by the American Bar Association for 2022 bar

exam takers, Seton Hall Law exceeded the New Jersey state average by more than 14

points with a pass rate of 85.71 percent compared to the state first-time pass rate

of 71.43 percent. Read more.

Meet Fatima M. Abughannam ’24: Center for Social Justice Scholar

Fatima M. Abughannam ’24 is dedicated to advocating for criminal justice reform, particularly

as it relates to indigent defense and wrongful convictions. As a first-generation

American and daughter to Palestinian immigrants, Abughannam recognizes the importance

of enhancing access to justice and promoting fundamental rights for everyone, including

members of underrepresented groups. Read more >>

Meet Shaindy Black ’25: Center for Social Justice Scholar

Shaindy Black ’25 is a first-generation weekend law student jointly pursuing her Master

of Social Work at the University of Pennsylvania. She plans to practice Family Law

using a trauma-responsive approach. Read more >>

Meet Eric Gallant ’24: Center for Social Justice Scholar

Eric Gallant ’24 was led to Seton Hall Law by his commitment to helping others. In

2017, Eric entered Norwich University and earned a commission into the U.S. Army.

In his junior year, he pivoted in his career and decided to take the LSAT. He began

his legal path in 2021 at Seton Hall and will begin active-duty service as a JAG in

the Army upon graduation in 2024. Read more >>

Meet Jamie Mitrovic ‘24: Center for Social Justice Scholar

Jamie Mitrovic ‘24 is committed to public interest by way of focusing on compliance

in environmental and energy law matters, while also serving BIPOC and other minority

communities around the tri-state area and beyond. More specifically, her primary plan

in the public service field revolves around the intersectionality of environmental

harms, disproportionate access to public services or environmental goods, and its

subsequent public health effects; all of which disproportionately affect BIPOC and

minority groups. Read more >>

Meet Myron Minn-Thu-Aye ’25: Center for Social Justice Scholar

Myron Minn-Thu-Aye ’25 grew up in Hong Kong. He majored in mathematics and computer

science at Williams College and completed his doctorate in mathematics at Louisiana

State University. He is a weekend student at Seton Hall Law and an Associate Professor

in Residence at the University of Connecticut, where he focuses on promoting accessibility

and active learning in mathematics. Read more >>

Seton Hall Law School Kicks Off Fourth Annual Gaming Law, Compliance, and Integrity

Bootcamp With Record Attendance

Seton Hall University School of Law’s groundbreaking program, the annual Gaming Law,

Compliance, and Integrity Bootcamp, is now underway. This year’s record attendance,

with over 100 participants, signals a growing demand in the gaming industry for in-depth

education about compliance, integrity, and ethics. Read more.

Leadership Fellows Program Receives Top Pro Bono Award

A group of nine Seton Hall Law students (and former students) received an award from

the New Jersey State Bar Association for their work in developing a series of informational

videos for survivors of domestic and sexual violence who represent themselves in restraining

order hearings. The students received the "Outstanding Law Student Pro Bono Award."

Read more.

Group of Nine Current and Former Seton Hall Law Students Will Receive Outstanding

Law Student Pro Bono Awards.

For the first time the NJSBA is awarding a student pro bono award titled the “Outstanding

Law Student Pro Bono Awards” and the recipients will be two teams of Seton Hall Law

students - one of the teams being Professor Paula Franzese’s team of Leadership Fellows.

Read more.

Senior Practitioner In Residence and 3L Student Win A Decisive Victory in the United

States Court of Appeals

Senior Practitioner in Residence Stephanie Norton of the Immigrants’ Rights/International

Human Rights Clinic at the Seton Hall Law School Center for Social Justice, along

with 3L student Michael Antzoulis, recently won a decisive precedential victory in

the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit on behalf of their indigenous

Guatemalan client, Selvin Saban-Cach. Read more.

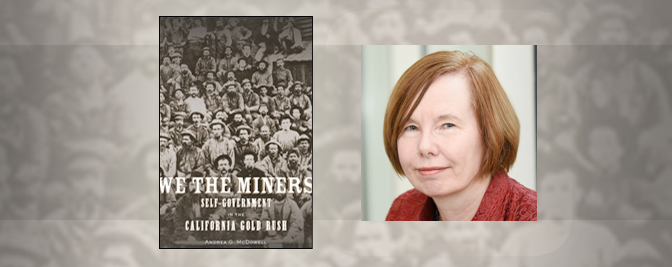

Professor Andrea McDowell's Book Named One of the Ten Best History Books of 2022 by

Financial Times

Professor Andrea McDowell’s book We the Miners: Self-Government in the California

Gold Rush was just named one of the ten best history books of 2022 by The Financial

Times. Read more.

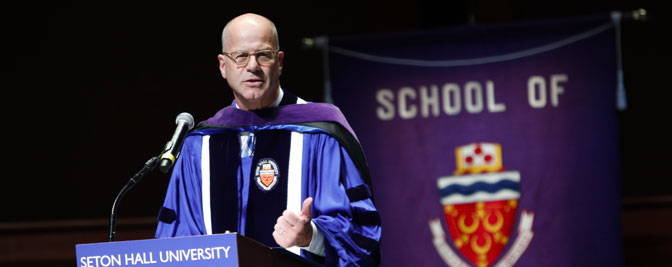

Dean Kathleen M. Boozang announces her return to the Seton Hall Law faculty and Professor

John Kip Cornwell is named Interim Dean

Dean Kathleen M. Boozang announces her return to the Seton Hall Law faculty and Professor

John Kip Cornwell is named Interim Dean. The entire Seton Hall community thanks Dean

Boozang for her tireless devotion to Seton Hall Law, and for her continued service

to the University — her academic home since 1990. Read more.

Center Faculty Work to Advance Sustainability of Key Members of Care Teams Who Improve

Access to Quality Care and Help Address Social Determinants of Health

Professors John V. Jacobi and Tara Adams Ragone continue to work with public and private

partners to build sustainability for workforce members who help address care and service

gaps for vulnerable populations. Read more.

New Jersey Funds Seton Hall Law Projects Focused on Addressing Health Care Equity

and Transition Assistance for Individuals with Developmental Disabilities

Professors John V. Jacobi and Tara Adams Ragone will spearhead work on two projects

earmarked in the State of New Jersey’s 2022-23 budget. Read more.

Impressive Health Law Faculty at Seton Hall Law

The Center for Health & Pharmaceutical Law’s dynamic and highly-regarded faculty research,

write and present on the leading health law issues including technology addiction,

leadership during crisis, medical misinformation, cost-effective analysis in medication

coverage, impact of COVID on undocumented individuals, the legal treatment of the

use of Pre-exposure prophylaxis, disability law, third-party accommodations, conflicts

of interested in doctor-patient relationships, illegal activities and criminality

of pharmaceutical and medical device companies, violation of federal Medicare and

Medicaid rules with overlapping surgeries, DOJ’s FCA resolutions and enforcements,

community health workers, and improving healthcare access to vulnerable populations

to list a few. Read about their recent accomplishments.

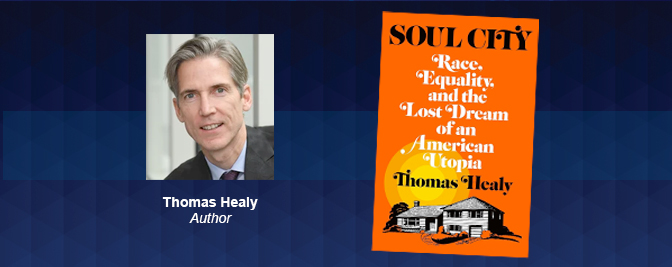

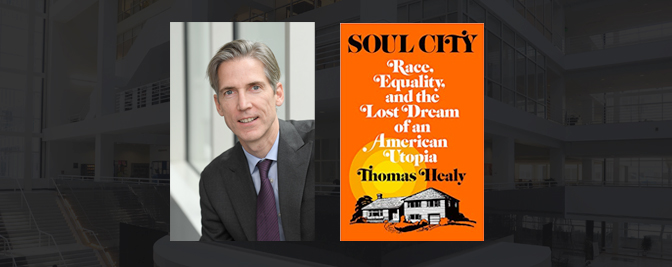

Professor Thomas Healy Receives 2021 Hooks National Book Award

Professor Thomas Healy has received the 2021 Hooks National Book Award for his most

recent book, Soul City. The Hooks Institute’s National Book Award is presented to

a non-fiction book published in the calendar year that best furthers understanding

of the American civil rights movement and its legacy. Read more.

Career Services Opens its Second-hand Career Closet for Students

The Office of Career Services is excited to announce the opening of its second-hand

career closet for students. One of the challenges some students face when entering

law school and pursuing career opportunities is accessing appropriate professional

attire for career fairs, interviews, networking events, and other career related needs.

The CS Boutique aims to provide students with attire that will boost their confidence

and exude professionalism. Read more.

Joel Silver, JD, '13 Receives the Dorothy M. Wolfe Award

Joel Silver is a Senior Associate General Counsel at Gilead Sciences, Inc. in Foster

City, CA where he is responsible for managing global legal support for regulatory.

Joel also serves as the Chair of Gilead’s Pro Bono program, which is focused on helping

survivors of domestic violence obtain protective orders as well as providing vital

legal services for juvenile immigration cases.

Alumnus, Judge Douglas Fasciale, ‘86, Nominated to Become Justice of NJ Supreme Court

Governor Phil Murphy announced his nomination of New Jersey Appellate Division Judge,

Douglas Fasciale, to become a justice on the New Jersey Supreme Court. He would be

the 42nd justice in the Court’s 75-year history. Judge Fasciale graduated Seton Hall

University with a bachelor’s in History in 1982, and he earned his J.D. from Seton

Hall Law School in 1986. Upon finishing school, he clerked for Superior Court Judge

John E. Keefe and thereafter worked as a trial lawyer in private practice for nearly

two decades. Read more.

New Flexible Course Format for Data Privacy and Security Compliance Certificate Program

Seton Hall University School of Law announces a new format for its Data Privacy and

Security Compliance Certificate Program with flexible Virtual Bootcamp Modules. Learners

will have the ability to bundle all bootcamp modules at a discounted rate or customize

and choose one or more modules to level-up privacy and security knowledge and skills.

Read more.

Dean Maldonado Co-Founds Latina Legal Academics Group Named in Honor of Graciela Olivárez

Associate Dean Solangel Maldonado co-founded and organized the Graciela Olivárez Latinas

in the Legal Academy Workshop (“GO LILA”) which launched this summer with a spectacular

inaugural meeting. Legal and cultural luminaries, including Supreme Court Justice

Sonia Sotomayor and Poet Laureate of Philadelphia Raquel Salas Rivera, spoke at the

event. By the time the 2-day conference concluded, over 70 current and aspiring Latina

law professors participated. Read more.

Student Loan Debt Information for Current Students and Alumni

Just days before the student loan repayment pause was set to expire, President Biden

announced an extension of the payment pause and interest accrual until December 31,

2022. President Biden also announced that he is canceling $10,000 in student debt

for millions of borrowers. Read more.

Sincere gratitude to The Honorable Esther Salas, U.S. District Judge for the District

of New Jersey for addressing incoming 1L students at Orientation

Seton Hall Law School extends its sincere gratitude to The Honorable Esther Salas,

United States District Judge for the District of New Jersey for addressing incoming

1L students at Orientation during a conversation with the Dean. Judge Salas spoke

candidly about her journey to and through law school, her experience as a federal

public defender and how she realized she wanted to become a federal judge. Read more.

Faculty Feature: Meet Professor Robert Boland

Assistant Professor Robert Boland joins Seton Hall Law as part of our Gaming, Hospitality,

Entertainment and Sports Law (“GHamES”) initiative and will focus on developing and

expanding Seton Hall’s Sports Law offerings. He brings a wealth of experience to this

endeavor, having most recently served as the Athletics Integrity Officer at the Pennsylvania

State University, where he oversaw the athletic program’s compliance with all legal

and ethical standards required by law, the University, the Big Ten and the NCAA. Learn more.

Seton Hall Law Places Highest number of Graduates on ROI Influencers: Law list

Seton Hall Law has earned the honor of producing the most graduates on the ROI Influencers: Law list. When interviewed by ROI, Dean Kathleen Boozang credits the strong alumni network

for part of the school’s success. Read more.

Professor Sheppard publishes op-ed on Supreme Court Reform at The Hill

“Recent polling revealed that [The Court's] public approval is at an all-time low,

and that was before its latest week of controversial rulings. Notably, the most pronounced

turn in favorability coincided with the recent shift to a 6-3 split in favor of Republican-appointed

justices.” Read more.

The Honorable Zoila Cassanova Appointed Director of Seton Hall Law School's Legal

Education Opportunity Program

We are pleased to welcome former L.E.O. student The Honorable Zoila Cassanova back

to Seton Hall Law School as the Director of the Legal Education Opportunity Program.

In this role, Judge Cassanova will be overseeing the administration of the Summer

LEO Institute and all LEO programming and events during the school year. Read more.

K. Anthony Thomas, ’95, Named Acting Federal Public Defender for the District of New

Jersey

Seton Hall Law Alumnus and Adjunct Professor, K. Anthony Thomas, ‘95, has been named

the Acting Federal Public Defender for the District of New Jersey. While occupying

this vital and prestigious position, Mr. Thomas will oversee the office’s representation

of indigent defendants in the federal district court. Read more.

Seton Hall Law Alumna, Evelyn Padin ’92, to become NJ’s next Federal Judge

On May 25th, the United States Senate confirmed Seton Hall Law alumna, Evelyn Padin,

’92, to serve as a federal judge on the U.S. District Court for the District of New

Jersey. Ms. Padin, who founded her own law practice, was recently the president of

the New Jersey State Bar Association. She was the first Latina to serve in the role.

She is currently the co-chair of the Diverse Attorneys of Seton Hall (DASH) Advisory

Committee.

Matthew Handley ’22 Selected for Prestigious Equal Justice Works Post-Graduate Fellowship

After graduation, CSJ Scholar Matthew Handley ’22, will start a fellowship at the

National Veterans Legal Services Program in Washington, D.C., sponsored by Lockheed

Martin Corp., as part of the Equal Justice Works Design Your Own Fellowship program.

Commitment to Social Change: Center for Social Justice Scholars Program (2021-22)

Each year, the Center for Social Justice selects students from those who have completed

their first year of law school to serve as CSJ Scholars. Selected students include

Sam Jerabek ’23 and Florencia Marino ’24. Learn more about the program and selected students.

The 3rd Annual Gaming Law, Compliance & Integrity Bootcamp Hosted Industry Experts

to Discuss Challenges and Adopt Best Practices

Seton Hall Law School’s Third Annual Gaming Law, Compliance & Integrity Bootcamp successfully

brought together regulators, operators, vendors, academics, law enforcement personnel,

and attorneys to discuss challenges facing the gaming industry and how to identify

and adopt best practices to promote compliant, ethical, responsible, and sustainable

gaming. Read more.

Philip R. Sellinger, U.S. Attorney for District of N.J. to Discuss Federal Anti-Fraud

Efforts in the Gambling Industry

Philip R. Sellinger will join the faculty of Seton Hall University School of Law’s

Third Annual Gaming Law, Compliance, and Integrity Bootcamp on May 18, 2022, in Newark,

New Jersey. Read more.

Data Privacy and Security – Top Challenge and Top Priority

Gibbons Institute for Law, Science & Technology and the Institute for Privacy Protection

presents a suite of virtual programs to equip compliance and legal professionals with

the knowledge they need to distinguish themselves as leaders in data privacy and security.

Learn more.

Michael Fasciale, 3L, Wins Multiple Accolades with Research on Student-Athlete Compensation

The latest research paper by Michael Fasciale, a 3L who is both Articles Editor of

the Seton Hall Law Review and President of the school’s Entertainment and Sports Law Society, has won multiple

honors. Fasciale wrote The Patchwork Problem: A Need for National Uniformity to Ensure an Equitable Playing

Field for Student-Athletes’ Name, Image, and Likeness Compensation, as a Comment for the Law Review. Read more.

Meet Professor Doron Dorfman: A Brief Q & A

The Law School is delighted that Professor Doron Dorfman is joining its ranks this

summer. While Professor Dorfman is known as an expert in Health and Disability Law,

he is an innovative scholar whose research defies simple categorization. Read more.

The Honorable Joseph A. Greenaway Highlights the Importance of Diversity in Supreme

Court Nominations

The judge used this year’s Diversity Speaks event to analyze the public response to

the nomination of the Honorable Ketanji Brown Jackson and carefully explained the

flawed assumptions of commentators’ critiques calling into question her qualifications

for the position after President Biden promised during his campaign to nominate a

black woman to the Court. Read more.

The Rise of Esports in New Jersey

Seton Hall Law School’s Assistant Dean Devon Corneal outlined potential legal issues

facing the esports betting sector for ROJ-NJ's March 9, 2022 article on the rise of

esports in New Jersey. Read more.

Impact Litigation Clinic Prevails in Precedential Second Circuit Qualified Immunity

Case

The Impact Litigation Clinic in the Center for Social Justice recently prevailed in

a noteworthy, precedential Second Circuit decision, Triolo v. Nassau County, involving

false arrest, qualified immunity, and municipal liability. The Impact Clinic provides

pro bono representation to litigants and serves as amicus curiae in cases presenting

important legal issues on behalf of impoverished and disempowered litigants, generally

in the federal courts of appeals or in the Supreme Court of New Jersey. Read more.

Faculty Feature -- Meet Professor Isis Misdary

Professor Isis Misdary will join Seton Hall Law in July to helm our Criminal Justice

Clinic. In this role, Professor Misdary will supervise clinical students on direct

criminal defense representation and broader strategic litigation. She will also lead

our efforts to design and pursue law reform projects in areas of dire need, such as

reentry, prisoner’s rights, expungement, or other aspects of criminal justice reform.

Read more.

Seton Hall Interscholastic Moot Court Board Wins Two National Moot Court Competitions

On March 5, 2022, Seton Hall’s Interscholastic Moot Court Board won TWO National Moot

Court Competitions, finishing First in both the Bryant Moore National Civil Rights Moot Court Competition and the Gabrielli National Family Law Moot Court Competition. Read more.

Expansion of Sports Betting in NJ and Around the Country

On March 4, 2022, Seton Hall Law School Assistant Dean Devon Corneal sat down with

the New Jersey Law Journal to discuss the expansion of sports betting in New Jersey

and the need for comprehensive and robust compliance education for gaming operators.

Read more.

Omicron and Crisis Standards of Care: How are Hospitals Responding to the Challenge?

This evening’s conversation arises from a patient care conflict that has received

national attention over the last weeks as it turned into a national conversation about

the allocation of limited resources during the COVID pandemic. In this interdisciplinary

conversation, experts in law, medicine, and ethics will explore how hospitals are

coping and how lawmakers are responding. Read more.

Housing Justice Project Releases Report on Landlord-Tenant Reform in New Jersey

With funding from the Legislature, Seton Hall Law School and Rutgers Law School established

the New Jersey Housing Justice Project at the start of the 2021-22 academic year.

The Housing Justice Project is expanding individual representation as it advocates

for broader social change, including work in the area of the implementation of landlord-tenant

reform and equity impact analysis in the landlord-tenant arena. Read more.

Has Big Tech become too big? Scholars and practitioners come together to explore these

questions

The Gibbons Institute for Law, Science & Technology and the Institute for Privacy

Protection is co-hosting this virtual conference to explore issues from U.S. and international

perspectives with leading academics, practitioners, and former regulators. Read more.

Seton Hall Law Receives $1 Million For Endowed Professorship From Rita And Kevin Marino

Seton Hall University's Chair of the Board of Regents, Kevin H. Marino, Esq. '84,

announced last month that he and his wife, Rita Marino, M.A.E. '94, are donating $1

million to establish an endowed professorship at Seton Hall University School of Law.

The professor occupying the endowed chair will be known as the Marino Tortorella &

Boyle Professor of Law, named for Marino's law firm. His partners, John D. Tortorella,

Esq. '99, and John A. Boyle, Esq. '00, are both distinguished Seton Hall Law alumni.

Read more.

Bernard Freamon Interviewed in One Thousand Years of Slavery: Documentary Airing on

Smithsonian Channel

To commemorate Black History Month, Uplands TV of the UK will air the documentary

One Thousand Years of Slavery – The Untold Story on the Smithsonian Channel. Four-Part

Docu-Series begins February 7, 2022.

Alumni Council Endowed Scholarship

When Daniel R. Levy ’04 learned the outsized impact on the Law School of increasing

its endowment, he swung into action. Dan was particularly engaged by the idea that

endowed scholarship funds could boost the Law School’s rankings by helping to recruit

and retain amazing students. He immediately turned to fellow Alumni Council members

Marc A. Calello ’89, Julian Leone ’04, and John Chiaia ’93 and the Chiaia Family who

are proud to announce the establishment of the Alumni Council Endowed Scholarship

fund. Read more.

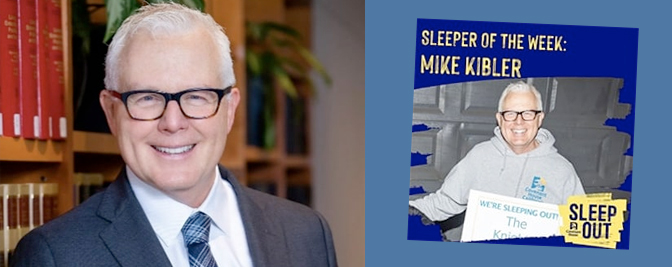

Seton Hall Law Proud: Michael Kibler B.A.’92, J.D.’97

Double Pirate, Michael Kibler B.A.’92, J.D.’97, is no stranger to servant leadership.

The core principles he learned as a student helped to prepare him to be the leader

he is today. In addition to being a long-standing supporter of Seton Hall Law, Mike

volunteers for worthy organizations such as Covenant House California. This fall marked

his 9th year serving on the Board and participating in the Executive Sleep Out for

CHC. Read more.

Series on Public Service Featuring former NJ Governor Chris Christie with former U.S.

Secretaries of Defense Leon Panetta and General James Mattis

The Christie Institute for Public Policy and Seton Hall University School of Law will

host a conversation with former United States Secretaries of Defense Leon Panetta

(2011-2013) and General James Mattis (2017-2018) at the Series on Public Service on

Thursday, December 16, 2021, from 7:00-8:00 p.m. on the importance and benefits of

bi-partisan public service to our nation. Learn more.

Thousands of Hours Dedicated to Fighting for the Rights of NJ Immigrants

The Immigrants’ Rights/International Human Rights Clinic of the Center for Social

Justice has been participating in New Jersey’s Detention and Deportation Defense Initiative

(DDDI) since its launch in 2018. The State-funded Initiative enables Legal Services

of New Jersey, American Friends Service Committee, Rutgers Newark Law School’s Immigrant

Rights Clinic, and Seton Hall Law School’s Immigrants’ Rights/International Human

Rights Clinic to provide free legal representation to indigent New Jersey immigrants

facing deportation. Read more.

Notable Alumni Accomplishments in Health Law

The Center for Health & Pharmaceutical Law is proud of its alumni accomplishments.

Our alumni continue to rise to prominence in their careers while uplifting their respective

industries and fields. Read full list of our alumni accomplishments.

Annual Health Law Symposium focusing on Long Term Care Services and Supports is now

Scheduled for March 1, 2022

The Center for Health & Pharmaceutical Law will host its Annual Health Law Symposium,

Long Term Care Services and Supports (LTSS): Payment and Caregiving on March 1, 2022.

Read more .

Professors John Jacobi and Tara Ragone Expand their Regulatory Reform Work on Several

Fronts with New CDC Grant

Professors John Jacobi and Tara Ragone are heading the Center for Health & Pharmaceutical

Law’s work as key partners in the execution of a new grant from the CDC: Community

Health Workers (CHW) for COVID Response and Resilient Communities. Through this three-year

grant, they will work with state agency and private sector partners to deploy CHWs

in prisoner reentry, behavioral health, and FQHC settings. Read more .

Third-year law students, Leslie Veloz, Bryan Hahm, and Julianna Dzwierzynski, took

Second Place finish at the National Health Law Moot Court Competition

The team defeated UNH, UNM, South Texas, Hastings, and Loyola Chicago before losing

by a slight margin to Texas Tech in the Finals. This is the third year in a row that

Seton Hall has been in the Final Round at the competition - with two victories the

last two years. Read more .

Thanksgiving Greeting from Dean Kathleen Boozang and Father Nicholas Gengaro

This Thanksgiving, our deepest gratitude is owed to the scientists and medical professionals

who worked nonstop to develop vaccines and treatments, and to public health experts

and government leaders who assure their wide and fair distribution. Read more.

Congratulations to Seton Hall Law Alum, Judge Michael Chagares '87

Seton Hall Law celebrates Judge Michael Chagares’ elevation to become Chief of the

Third Circuit, effective December 4, 2021. This is an extraordinary accomplishment

that shows the power of a Seton Hall Law degree. Read more.

Updates relating to Public Service Loan Forgiveness / Loan Repayment

After nearly a two-year pause, federal student loan payments are scheduled to resume

early in 2022. Additionally, your servicer may have changed since you graduated.

We are happy to help you navigate various repayment options. Learn more about recent changes.

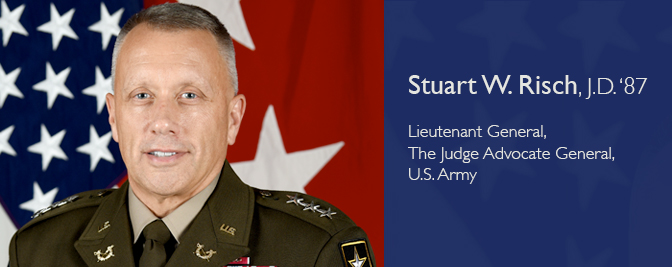

An Honor and a Privilege: Veterans Day with The Judge Advocate General of the US Army

Seton Hall Law School proudly hosted Lieutenant General Stuart W. Risch, J.D. ’87,

The Judge Advocate General of the United States Army on November 10, 2021, as part

of Veteran’s Appreciation Week. LTG Risch spoke about the meaning of Veterans Day,

and he explained how law students can get involved in the JAG Corps and why they should

consider careers in service. LTG Risch also provided a stellar example of the meaning

of Veterans Day through his heartfelt words and demeanor, both of which encompassed

a common theme – gratitude. Read more.

37th Annual Red Mass

Named from the red vestments used in celebrating the Mass and from the red robes worn

by judges in the Middle Ages, the Red Mass is celebrated at the beginning of the judicial

year to invoke God’s blessing and guidance in the administration of justice. The 2021

honoree recipient of the St. Thomas More Medal, The Honorable Joseph A. (Drew) Dickson

U.S.M.J. (retired) ’81 was joined by gift presenters Susan A. Feeney, Jeralyn Lawrence

’96, and Eileen M. O’Connor ’88 (not pictured), and readers Patrick D. Tobia ’85 and

the 2020 Red Mass honoree, K. Anthony Thomas ’95. View photos.

Law and the Technologies of Life Colloquium (Fall 2021)

The Institute for Privacy Protection and the Gibbons Institute of Law, Science & Technology presents the Law and the Technologies of Life Colloquium. The Fall 2021 Colloquium is hosted by Professor Gaia Bernstein and will feature academic

speakers presenting cutting-edge projects on how new technologies change the way we

live and the role of the law in accommodating these technological innovations. Read more.

Seton Hall Law Bids Two Legal Beacons Farewell

Professors Charles Sullivan and Mark Denbeaux were instrumental in making Seton Hall

Law the institution it is today. Together with others of their generation, they were

instrumental in creating and executing the vision that produced One Newark Center.

With all the gratitude for their years of service, teaching, practice, and pioneering,

we thank Professors Sullivan and Denbeaux and wish them utmost happiness and fulfillment

in the next chapter of their lives. Read more.

Assistant Dean of Career Services June K. Forrest

Assistant Dean of Career Services June K. Forrest has transformed Seton Hall Law’s

presence in New Jersey since her arrival in 2016, working with students and graduates

to discover their pathway to launching their careers, whether in the law or another

professional universe. Under Dean Forrest’s leadership, the Office of Career Services

(OCS) has become a place that welcomes all students. In partnership with our ever-loyal

alumni, the OCS team has captured employers across the New Jersey and New York marketplaces

and expanded Seton Hall Law’s reach to the many states from which admissions has increased

its recruitment. Read more.

Dean Kathleen M. Boozang Named as State Higher Education Influencer by NJ-ROI

ROI-NJ issued its annual “Influencers List,” for Higher Education, and Dean Kathleen

Boozang was given the honor of being declared an influencer among Deans and Directors

of Higher Educational Institutions. Read more.

Amicus Brief Filed by the Center for Social Justice Informs New Jersey Supreme Court

Decision

Christopher Dernbach’21 and Mikayla Berliner ’21, students in the Impact Litigation

Clinic in the Center for Social Justice (CSJ),drafted an amicus brief in the Supreme

Court of New Jersey that played a significant role in the Court’s decision in State

v. McQueen. Professor Jon Romberg supervised the students and argued before the Court.

Read more >>

Commitment to Social Change: Center for Social Justice Scholars Program

Willingness to work determinedly for those in need. Perseverance in the face of challenge.

These are the characteristics that define a Seton Hall Law School Center for Social

Justice (CSJ) Scholar. In the Fall semester of each year, the CSJ selects students

from those who have completed their first year of law school to serve as CSJ Scholars.

Selected students include Mia Dohrmann '22, Hannah Eaves '22, Matthew Handley '22

and Prubjot Kaur '22. Learn more about the program and selected students.

Meet Mia Dohrmann ’22: Center for Social Justice Scholar

Mia Dohrmann ’22 was led to Seton Hall Law by the drive to serve communities and further

the cause of social justice. In 2012, she entered college in Baltimore with a goal

to become a doctor serving patients in disadvantaged communities. When she deviated

from the pre-medical path, she knew that she needed to utilize her passion for serving

others in a different way. After her graduation in 2016, she embarked on a 70-day

team bike ride from Baltimore to Seattle with the 4K for Cancer. During her journey,

her team met countless individuals affected by cancer who were still determined to

find a cure and help others facing tough diagnoses. Read more >>

Meet Hannah Eaves ’22: Center for Social Justice Scholar

Hannah Eaves ’22 came to Seton Hall Law to learn how to become an advocate for marginalized

members of our society. Eaves has focused her advocacy on the intersectionality between

socioeconomic status, health, race, and the law. “The social determinants of health

affect individuals’ access to economic resources, their statistical likelihood of

incarceration, and even their access to the franchise. We must understand all these

variables to develop the effective tools for changes,” said Eaves. She is concentrating

in Health Law, with the hopes of pursuing a career dedicated to ensuring health equity

for those with who have historically been underserved by the system and advocating

for anti-racist health policy. Read more >>

Meet Prubjot Kaur ’22: Center for Social Justice Scholar

Prubjot Kaur ’22 is a first-generation law student who aspires to defend those disenfranchised

by the current legal system. “Minorities in the United States constantly undergo daily

interactions which exhibit the profound racism prevalent in our society. Racist experiences

have empowered me to vocally oppose bigotry of all forms and be committed to dismantling

systems of oppression to promote access to justice,” said Kaur. Read more >>

Ariel Risinger, JD ’15, Successful Transactional Attorney and Champion Powerlifter

Approaches All Challenges with the Same Mindset

Ariel Risinger, JD ’15, an associate attorney at Day Pitney, recently made headlines

in Law360 Pulse for her accomplishments in competitive powerlifting. When asked about

her approach to competitions she told Law360 Pulse "I'm just going to go out there

and do my best, regardless if it's as a lawyer, or in powerlifting, or in whatever

I do." Read more >>

Professor Lubben Testifies before Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources

Professor Stephen Lubben testified regarding a bill that will require professionals

retained in Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy to disclose their stakes in connection with the

case. Read more >>

Professor Healy Quoted in New York Times Article on Obscenity Ruling

Professor Thomas Healy featured in a New York Times story on a noteworthy First Amendment

case. Read more >>

Amicus Brief Filed by the Impact Litigation Clinic Significantly Informs New Jersey

Supreme Court Decision

Luke Dodge ’21, Fran Mangot ’21, and Avi Muller ’21, under the auspices of the Impact

Litigation Clinic in the Center for Social justice, filed an amicus brief that significantly

informed the New Jersey Supreme Court’s decision in the very important case of State

v. Andujar; Professor Jon Romberg argued before the Court. Read more >>

Stuart W. Risch, J.D. ‘87, Promoted to Lieutenant General and The Judge Advocate General

of the United States Army

On July 16, 2021, in a ceremony surrounded by family and friends, Seton Hall Law School

Alum Stuart W. Risch, J.D. ’87 was promoted to Lieutenant General (LTG) and sworn

in as The 41st Judge Advocate General of the United States Army. LTG Risch now leads

a Regiment 10,000 strong, comprised of judge advocates, enlisted paralegals, warrant

officers, as well as civilian attorneys and paraprofessionals. Read full story >>

Seton Hall Law Alum, Domenick Carmagnola ’88, Sworn In as NJSBA President

Seton Hall Law congratulates Domenick Carmagnola ’88, Member at Carmagnola & Ritardi,

LLC, on being sworn in as the 123rd President of the New Jersey State Bar Association

for 2021-2022. Domenick values hard work and dedication and is not shy about strong

advocacy for the legal profession as we emerge from the pandemic. Hear more from Domenick’s installation speech on May 26.

Seton Hall Commemorates Official Juneteenth Holiday

Seton Hall University will be celebrating the official commemoration of Juneteenth

as a holiday in New Jersey. In September 2020, Governor Murphy signed legislation

formally designating Juneteenth as a recognized state and public holiday, which will

occur annually on the third Friday in June. Read more >>

Seton Hall Law Celebrates the First Graduating Class of the Part-Time JD Weekend Program

Weekenders volunteered time at the local soup kitchen and gave back to the Newark

community; they worked on behalf of real clients through the Seton Hall Law’s Center

for Social Justice and wrote for Incarcerated Persons Workforce Re-Entry; and they

visited detainees at the border to provide legal services. Many students were instrumental

in starting and reviving new committees and student organizations throughout the law

school, with some assuming prominent leadership positions on the Law Review and in

the Student Bar Association, and achieving high placements in in Mock Trial and Moot

Court competitions. Read more.

Professor Murray and the Law Review Share Words of Encouragement with the Class of

2021 on What it Means to Become and Practice as a Lawyer at the Present Time

Congratulations Seton Hall University School of Law Class of 2021! We’ve come a long

way since 1L. Each and every one of us should be so proud of all that we’ve accomplished

during our time at Seton Hall. Professor Murray gave a stirring speech at the 2020

orientation on what it means to become and practice as a lawyer during these times.

Read more >>

Address by Member of the Class of 2021, William Shubeck, J.D. ’21

"You can’t let people rent space in your head. Don’t focus on how seemingly far ahead

or behind you are. The more time you spend worrying about someone else, the less time

you spend concentrating on your race. And, if you trust in these words, when you cross

that finish line, I promise you’ll be happy." Read full address >>

Address by Member of the Class of 2021, Jordan Stefanacci, J.D. ’21

"Remember the classmates who helped you get there and remember that you did not do

this alone. We are all very fortunate to be receiving a degree from a University where

the sky really is the limit...if there is one thing you take away from this speech,

let it be this. Work hard, but don’t work so hard that you miss out on all of the

amazing things life has to offer. Because at the end of the day the things that give

our lives meaning are the people we surround ourselves with and the memories we make

along the way. The hero inside all of us should never fear living each moment to its

fullest." Read full address >>

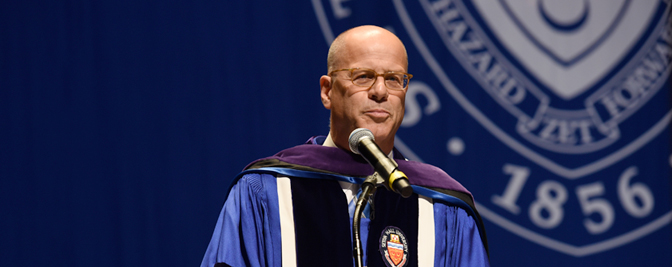

Commencement Keynote Address delivered to the Class of 2021 by Kevin H. Marino, Esq.,

Founding Partner, Marino, Tortorella & Boyle, P.C.

"For someone on the right path, work is a central component of a life that includes

ample time for family and friends, for volunteerism and community service, and for

whatever else appeals to the mind and soul, be it music or art, prayer or literature,

film or sports, all of the above or countless other pursuits. Well‐rounded, happy

lawyers can and must have such things in their lives. You really can write the brief,

argue the appeal, negotiate the contract, lobby the legislature and still coach your

son or daughter’s basketball team. I promise." Read more.

Address by Member of the Class of 2020, Tatiana Laing, J.D. ’20

"It is my hope that none of you ever forget the spot you have earned in this profession.

May none of us forget where we have come from and the lessons we learned together

in law school. If we remember this journey as we move up in our careers, I have no

doubt that we will continue to make an impact for the better in every courtroom, law

firm, or board room that we find ourselves in." Read full address >>

Commencement Keynote Address delivered by Madeline Cox Arleo, J.D. ’89, United States

District Judge

"Seton Hall lawyers are exceptional, and genuinely good and decent human beings.

And by graduating today, you are part of that enduring legacy of excellence and goodness.

Be proud of it and cherish it, like I do. You are a Seton Hall lawyer. It means

something. And because of that, each one of you is especially prepared to change

your corner of the world for the better." Read full keynote address.

Law Professor Thomas Healy appears on two top national podcasts, Radiolab and Code

Switch (NPR)

In one program, Thomas Healy explores the failed social experiment of a community

based on principles of black economic empowerment, Soul City. In another, he examines

the mystery of one judge’s change in position about free speech, how that moment changed

the minds of others, and whether it’s time to change minds again. Read more >>

Asian Pacific American Law Students Association Celebrates Asian American Heritage

Month

The Asian Pacific American Law Students Association (APALSA) at Seton Hall Law have

been busy hosting events and programs in celebration of the Asian American Pacific

Islander Heritage Month. Read more >>

Law Professor Marina Lao on Auto Dealer’s Argument About Protecting Consumers’ Buying

Options

Professor Marina Lao, who specializes in Antitrust Law, was interviewed by Christine

Hatfield on April 15 (WGLT 89.1 FM, NPR from Illinois State University) and provides

insight on what is best for consumers in latest nationwide debate over the options

consumers have to buy cars. Read more .

Professor Heather Payne, an Emerging Leader in Environmental Law

Law Professor Heather Payne is an emerging leader in the areas of environmental law,

energy law, evolving regulatory policy, and the implications for property, both real

and intellectual. Read more >>

Seton Hall Law congratulates Rick Little on new appointment to Superior Court Judge

in Essex County

Professor Alvin Richardo (Rick) Little has been appointed to be a Superior Court Judge

in Essex County. Throughout his distinguished career, Judge Little has carried himself

with grace and demonstrated a strong work ethic and commitment to justice, fairness,

and equity. Join us in congratulating Judge Little. Read more >>

Professor Freamon creates website directed at abolishing slavery in the Muslim World

Professor Emeritus Bernard K. Freamon has launched a website, entitled Ijmāʿ-on-Slavery.

The ambitious enterprise provides the first online platform for Muslim thinkers to

reach an agreement or “ijmāʿ” that slavery must be abolished under the Shari’a—the

authoritative corpus of texts on Islamic law and ethics. Dr. Freamon argues that the

Islamic legal concept of ijmāʿ (“consensus”) has the capacity to bring about powerful

social change. Read more >>

Seton Hall Law Clinic Wins Case Before New Jersey Supreme Court: Haley v. Board of

Review

Seton Hall University School of Law’s Center for Social Justice (CSJ) prevailed in

Haley v. Board of Review, a case challenging the denial of unemployment benefits to

Newark resident Clarence Haley based upon his pretrial incarceration for charges later

dismissed. The New Jersey Supreme Court reversed the Appellate Division’s decision

denying Haley benefits and held that under New Jersey’s Unemployment Compensation

Law “pretrial detention is not an absolute bar” to benefits. Read more >>

Professor Margaret Lewis is Featured in World Media

As the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party approaches this July, officials

and media outlets from around the globe are contacting Law Professor Margaret "Maggie"

Lewis to provide her expertise and analysis of the legal policy implications today

concerning China and Taiwan with an emphasis on criminal justice and human rights.

Read more >>

Seton Hall Law Named a 2021 Top 50 Go-To Law School

Seton Hall Law ranked 47th in the country in the National Law Journal/LAW.COM list of Go-To Law Schools. The

survey ranks schools according to the percentage of graduates who get jobs at the

largest 100 law firms in the country. Read more >>

Inspirational Women of Seton Hall Law School

Celebrating Women in the Law: Seton Hall Law is incredibly proud to highlight some

of the recent achievements of its accomplished faculty in celebration of International

Women’s Day.

Read more >>

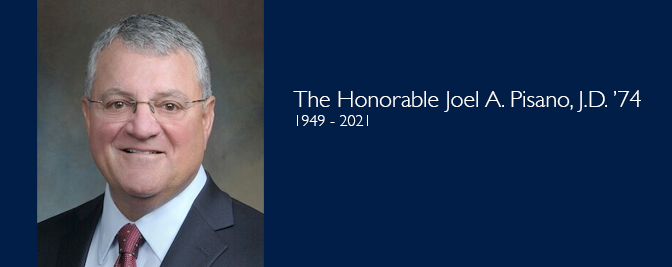

In Memoriam --The Honorable Joel A. Pisano, J.D. ’74 (1949-2021)

Seton Hall University School of Law mourns the passing of the Honorable Joel A. Pisano,

J.D. ’74, who was an adjunct professor and served as a federal judge in The United

States District Court for the District of New Jersey over the span of two decades.

Read more >>

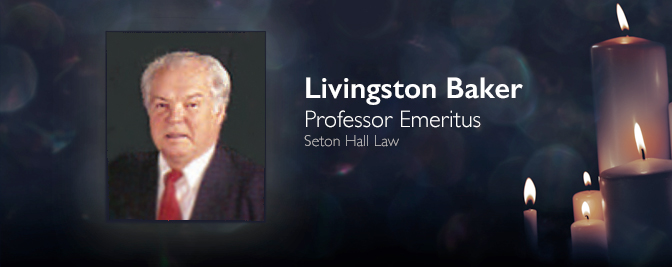

Tribute to Livingston Baker, Professor Emeritus – A Generous Heart

Seton Hall University School of Law is saddened by the death of Professor Emeritus

Livingston Baker who passed away recently. He specialized in teaching property law

and public and private international law courses. Having taught over thirty years

at Seton Hall Law, including guest lectures at the School of Diplomacy, his teaching

repertoire was vast. Most importantly, Professor Baker’s discussions, both in class

and with faculty colleagues, were always informed by a moral, philosophical, and learned

perspective. Read more >>

Healy's Book Receives National Acclaim

Professor Thomas Healy’s new book, “Soul City: Race, Equality, and the Lost Dream

of an American Utopia”, which explores the rise and fall of Soul City, a concept developed

and nurtured in the 1970s by civil rights leader Floyd McKissick, is receiving rave

reviews.

Craig Carpenito named partner of King & Spalding joins Seton Hall Law Board of Visitors

Seton Hall Law congratulates Craig Carpenito '00, who has joined King & Spalding as

a partner in the firm’s Special Matters and Government Investigations practice group

in the New York office. Mr. Carpenito has also joined the Seton Hall Law Board of

Visitors. Read more >>

157 Law Deans Publish Rare Joint Statement on the 2020 Election and Events at the

Capitol

On January 12, 2021, 157 Law School Deans from schools across the country published

a statement addressing the 2020 election and the events that took place in the United

States Capitol last week. The statement marks a rare occasion. It is unusual for such

a diverse group of law deans to come together to speak as one on an issue that falls

outside the ambit of legal education. Read more >>

Professor Jenny-Brooke Condon and the Center for Social Justice Making Significant

Impact on Law Reform

Professor Jenny-Brooke Condon presented an argument before the New Jersey Supreme

Court challenging the State’s denial of unemployment benefits to an individual who

was detained on charges that were subsequently dismissed. Read more >>

Law Students Research the Impact of COVID-19 on Survivors of Domestic Violence in

New Jersey

During the Fall 2020 semester, faculty in the Seton Hall Law School Center for Social

Justice (“CSJ”) worked closely with law students researching the impact of COVID-19

on survivors of domestic violence in New Jersey in conjunction with the non-profit

organization Partners for Women and Justice (“Partners”). Read more >>

Seton Hall Law congratulates alumnus Craig Carpenito ’00 on his outstanding service

as New Jersey’s top Federal Prosecutor on the occasion of announcing his resignation

as U.S. Attorney

US Attorney Carpenito operationalized a vision for the office that positively impacted

the lives of the citizens of New Jersey, which he accomplished through significant

organizational change and strengthened relationships with state and city law enforcement.

Read more >>

Law Professor Paula Franzese Named a Top Woman in Law by the New Jersey Law Journal

Law Professor Paula Franzese has been named one of the "Top Women in Law" by the New

Jersey Law Journal. Considered "the statewide legal authority" of the New Jersey legal

community, the New Jersey Law Journal has been published since 1878. The award, which

was last bestowed in 2018, was through the submission of nomination letters and curricula

vitae and the deliberation of a panel. The criteria was "impact." There are more than

75,000 lawyers in New Jersey; twenty women were honored. Read more >>

COVID-19 Challenge Trials Podcast

As an extension of our past series on vaccines, Seton Hall University School of Law

Professor Carl Coleman discusses the ethical issues of COVID-19 vaccines challenge

trials with Dr. Bryan C. Pilkington of the School of Health and Medical Sciences at

Seton Hall University. Read more & listen to podcast >>

Professor Jennifer Oliva, winner of the 2021 Health Law Community Service Award for

the AALS Law, Medicine and Health Care Section

Professor Jennifer Oliva has been awarded the prestigious 2021 Health Law Community

Service Award for the AALS Law, Medicine and Health Care Section. The Section annually

gives an award to recognize outstanding contributions of law teachers in the service

of health law. The award is designed to recognize a wide variety of community service

activities, including pro bono litigation, legislative advocacy, consulting on public

initiatives, and other major projects. Through her extensive scholarship, grant work,

and public advocacy including amicus briefs, Professor Oliva has championed issues

of justice for people with opioid use disorder (and other substance issues) and for

veterans with disability issues. She has also focused her advocacy in the areas of

privacy rights and race implications of COVID-19 response efforts. Professor Oliva's

service to law students and to the community-at-large is admirable and extensively

described in the award announcement. She is a graduate of the United States Military

Academy at West Point, an Army combat veteran, and an honors graduate of the Georgetown

University Law Center. Read more >>

Jay E. Town '98: A Veteran with an Impeccable Military Service Record and Professional

Legal Career

Seton Hall Law veterans enrich our community because they exemplify what it truly

means to give back. Their strength and selflessness inspire us to be better versions

of ourselves. This call is certainly a strong reason why they choose to pursue a legal

career – to serve generously again in the interests of transforming the lives of others

through the power of the law. November is National Veterans and Military Families

Month. As we take a moment to reflect on the blessings we have because of their sacrifice,

we realize the importance of telling their personal stories... Read more >>

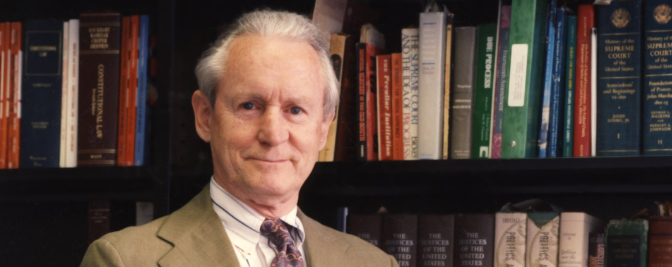

Professor Thomas Healy in the Spotlight

Professor Thomas Healy is a nationally renowned legal expert in the areas of constitutional

law, freedom of speech, legal history, civil rights, and federal courts. He is entering

his eighteenth-year teaching at Seton Hall Law. In addition to being a stellar teacher,

Healy’s background in journalism coupled with his passion for the law makes him one

of the most gifted legal scholars in the country. In his latest book, Soul City:

Race, Equality, and the Lost Dream of an American Utopia, Healy combines his passions

to tell the story of an attempt in the 1970s to create a city dedicated to the promise

of racial equality in the heart of Klan Country.

Getting the Most out of Your VA Education Benefits

Are you a Veteran or Military-Affiliated student? Are you looking to pursue higher

education and want to hear how you can take advantage of the VA's Education Benefits.

Any Veteran or Military-Affiliated student who is interested in pursuing any type

of higher education degree should attend this virtual information session on November

11, 2020 (12:00–13:30 p.m.) Read more and register to attend virtual Information Session >>

Professor Paula Franzese on RBG, Supreme Court and Amy Coney Barrett (One-on-One with

Steve Adubato)

Professor Paula Franzese sat down on with Steve Adubato to discuss RBG, the role of

the U.S. Supreme Court and Amy Coney Barret. Watch the recorded remote edition of One-on-One with Steve Adubato, aired on October 14, 2020.

Community Conversation led by BLSA, "State of Affairs: Ballot Edition – Voting in

2020"

This community conversation addressed the history of voting rights in this country,

including the ratification of the 14th Amendment, the passage of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965, and the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Shelby County v. Holder, where

the court struck down a formula at the heart of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

APALSA hosts Virtual Conversation Advancing Goal of Pursuing Opportunities to Build

Bridges within and outside Seton Hall Law School

On September 8th, 2020, the Seton Hall Law Asian Pacific American Law Students Association

(APALSA) hosted “Asian Americans at a Crossroads: COVID-19, #BLM, Discrimination,

and Allyship,” a virtual conversation featuring Queens College President Frank H.

Wu and moderated by Professor Marina Lao.

Professor Margaret Lewis to present on panel discussing the Justice Department's China

Initiative

“The Human and Scientific Costs of the ‘China Initiative’” is the first of a series

of webinars to examine the ramifications of the U.S. Justice Department’s “China Initiative”

on the civil rights and security of Chinese Americans, Chinese immigrants, and Chinese

Nationals working in the U.S., as well as the consequences for the broader American

society. Read more >>

Judge Thomas Moore ’80 and Alessandra Moore ’21: A Father and Daughter Seton Hall

Law Connection

Many alumni children grow up as part of the Seton Hall Law network. For those inspired

to follow in their parents’ footsteps, it is no surprise that so many of them choose

Seton Hall Law because they know firsthand the caliber of the faculty and the honored

commitment of producing practice-ready lawyers. While Seton Hall Law has always been

a transformational place, its national reputation has grown, making it even more of

a draw for next generation lawyers. Read more >>

Class of 93 Alums Nancy Shore DiLella and Simone Handler Connect John DeFuria, 3L

Health Law Student with Remote Internship

Seton Hall Law hires Seton Hall Law. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the loyalty

of the Seton Hall Law community has remained steadfast in securing internship and

employment opportunities for students to gain practical hands-on experience, whether

remote or in-person. Read more >>

Newly Appointed Essex County Bar President Kevin Walsh ’98 Recaps First 100 Days in

Office

Kevin G. Walsh ’98 was appointed as the 123rd President of the Essex County Bar Association

(ECBA) on May 11, 2020. The Honorable Sallyanne Floria ’78, Assignment Judge in the

Essex County Vicinage, swore in Walsh. His appointment marks the third consecutive

appointment of a dynamic Seton Hall Law alum to hold the position – Matthew Schultz

’02 (2019-20), Raj Gadhok ’99 (2018-19), and Francine Aster ’87 (2017-18). Walsh Co-Chairs

the Government and Regulatory Affairs Department for Gibbons, P.C. and is a member

of the firm’s Executive Committee. Read more >>

Marc Larkins ’97 and Evelyn Padin ‘92 Lead Diverse Attorneys of Seton Hall Advisory

Committee (DASH)

Marc Larkins ’97 and Evelyn Padin ‘92 serve as the Co-Chairs of the Diverse Attorneys

of Seton Hall (DASH) Advisory Committee. The DASH Advisory Committee is comprised

of more than 25 alumni from various practice areas, geographic locations, and diverse

backgrounds with the goal to collaborate with Seton Hall Law on innovative ways to

enhance diversity, inclusion and equity initiatives.

Thank you Justice Ginsburg

We have lost a great legal mind who transformed the lives of many for the better by

virtue of her work has an attorney, law professor and Supreme Court Justice. May

you be inspired by her example and tenacity. Read more >>

COVID-19 Vaccines: Who will be exempted from a COVID-19 vaccine?

The faculty in the Center for Health & Pharmaceutical Law continue to work closely

with law students who are researching COVID-19 topics. We are pleased to bring you

this ongoing series, which includes articles that the students have written based

on their research. In her fourth article, Jessica Kriegsfeld explores whether exemptions

are likely to be available if states mandate a COVID-19 vaccine once it is available

to be distributed. She consulted with Professor Angela Carmella and Professor Carl

Coleman on her research. Read full article >>

NJ Supreme Court Firsts for Seton Hall Law

The first Seton Hall Law appointee to serve on the New Jersey Supreme Court is retiring.

Associate Justice Walter F. Timpone ’79 was sworn-in by Chief Justice Stuart Rabner

on June 2, 2016 at Seton Hall Law School, and has served the Court and the citizens

of New Jersey with honor and dignity. In November, Justice Timpone will reach the

mandatory retirement age. The New Jersey State Senate yesterday afternoon unanimously

confirmed Governor Phil Murphy’s nomination for Fabiana Pierre-Louis to succeed Justice

Timpone. Read more >>

Privacy and Intellectual Property in the Age of Coronavirus

Seton Hall Law’s Institute for Privacy Protection and Gibbons Institute of Law, Science

& Technology will host an online event on “Privacy and Intellectual Property in the

Age of Coronavirus” on September 17 from 12:00 -2:30 pm EST. Speakers will include

legal academics, practitioners, and government officials who will discuss the impact

of the COVID-19 pandemic on privacy and intellectual property. Read more & Register >>

Insights on President Trump’s Executive Order on the Payroll Tax

Professor Richard Winchester explains executive order signed by President Donald J.

Trump on August 8, directing the government to defer a portion of the tax withheld

from the paychecks of certain workers. Legal challenges are expected. However, if

implemented, the measure would provide very limited relief while leaving workers with

a huge tax debt that they must pay at the end of the year. Read more >>

COVID-19 Vaccines: Can the government mandate COVID-19 vaccination?

The faculty in the Center for Health & Pharmaceutical Law continue to work closely

with law students who are researching COVID-19 topics. We are pleased to bring you

this ongoing series, which includes articles that the students have written based

on their research. In her third article, Jessica Kriegsfeld explores whether the

government can mandate a COVID-19 vaccine once it is available to be distributed.

She consulted with Professor Carl Coleman, Professor Angela Carmella, and Professor

Jennifer Oliva on her research. Read more >>

Major League Baseball Names Michele Meyer-Shipp '95, Chief People & Culture Officer

“Michele has dedicated her career to establishing diverse, inclusive, and engaging

workplaces. She brings an unparalleled ability to create meaningful cultures and relationships

among employees by implementing policies that help people connect with one another

and embrace the power of diversity to improve business operations,” says Dean Kathleen

M. Boozang. “Major League Baseball did not just hire a Seton Hall Law alum. MLB hired

a stellar and accomplished advocate for equity, justice, and fairness. Read more >>

Church Restrictions in the Age of COVID-19: Reasonable or Discriminatory?

Many states have pandemic public health guidelines specifically for houses of worship,

including bans on singing during indoor services with occupancy limits. Yet, no other

indoor operations have similar bans. Seton Hall University School of Law Professor

Angela Carmella explores the relevant First Amendment issues related to public health

restrictions on churches. She also reviews the recent religious freedom litigation

related to COVID19, including several cases decided by the U.S. Supreme Court. Read more >>

COVID-19 Vaccines: Who Will Pay For Them?

The faculty in the Center for Health & Pharmaceutical Law has been working closely

with law students who are researching COVID-19 topics. Some students are also enrolled

in the course, COVID-19: Current Topics in Pandemic Law & Policy. We are pleased to

present this series, which includes articles that the students have written based

on their research. In her second article, Jessica Kriegsfeld explores who will pay

for the COVID-19 vaccine once it is available to be distributed. She consulted with

Professor Carl Coleman and Professor John Jacobi on her research. Read article >>

Ask a Compliance Officer Series: Special Guest Commentators – Gary Giampetruzzi and

Jane Yoon Discuss Conducting Investigations During COVID-19

In the latest installment of the Center for Health & Pharmaceutical law's Ask a Compliance

Officer Series, Professor Jacob Elberg interviews Gary Giampetruzzi and Jane Yoon,

partners at Paul Hastings. The discussion focuses on how the ability to conduct investigations

has been impacted by COVID-19, and how this has evolved over the course of the pandemic.

They discuss navigating both restrictions and re-openings, which have varied widely

across locations. Other interview questions explore how to approach data collection

for investigations, how compliance resources have been reallocated and prioritized

in the current environment, and the expectations of government enforcers during recent

investigations. They also comment on impacts to compliance training and the current

opportunity for companies to focus on it. Read article >>

COVID-19 Vaccines: Who Should Get the COVID-19 Vaccine First?

The faculty in the Center for Health & Pharmaceutical Law has been working closely

with law students who are researching COVID-19 topics. Some students are also enrolled

in the course, COVID-19: Current Topics in Pandemic Law & Policy. We are pleased to

present this series, which will include articles that the students have written based

on their research. In this first article, Jessica Kriegsfeld addresses the question

of which populations should be prioritized to receive a vaccine once it is approved

and available. She consulted with Professor Carl Coleman on her research. Read article >>

Law Professor Margaret Lewis Elected Life Member of the Council on Foreign Relations

The Council on Foreign Relations has elected Seton Hall University School of Law Professor

Margaret K. Lewis to life membership. Professor Lewis has dedicated her legal career

to international law, human rights and criminal justice, specifically in China and

Taiwan. Read more >>

Health Law Weekly Roundup: Week Ending July 10, 2020

This week's COVID-related news includes proposed safety guidelines created by an advocacy

coalition seeking to preserve family presence at healthcare facilities during the

pandemic. While the U.S. government funded a leading vaccine candidate, the FDA

approved a test to quickly distinguish seasonal flu from COVID-19 and will soon be

reviewing a wearable device that can detect and monitor COVID infections. In other

health law news, the US Supreme Court ruled on a religious exemption to the Affordable

Care Act. For these updates and others, review our Health Law Weekly Roundup. Read more >>

Third Update: New Course on COVID-19 Law and Policy

Exciting and interesting wide-variety of topics were explored during weeks four and

five of Seton Hall’s newest course COVID-19: Current Topics in Pandemic Law and Policy.

Professor Jennifer D. Oliva's latest update on new course focused on privacy and telemedicine

and COVID-19 therapeutics and clinical trials. The class also discussed pandemic

impacts on small businesses, workers, labor laws, criminal, policing, and prisons.

Read more >>

National Law Journal Ranks Seton Hall Law #1 in the Nation for 2019 State and Local

Clerkships

The National Law Journal has released employment data for 2019 law school graduates,

Seton Hall Law remains one of the nation’s top law schools on this critical metric.

Seton Hall Law ranks #1 of more than 200 law schools in placing their 2019 graduates

into State & Local Clerkships, and #20 into Full-time law jobs. Read more >>

Second Update: New Course on COVID-19 Law and Policy

This summer is flying by at an alarming pace. This is the 2nd update on Seton Hall’s

newest course COVID-19: Current Topics in Pandemic Law and Policy and the class has

been absolutely terrific. Professor Jennifer D. Oliva provides an update and recommended

readings. Read more >>

Health Law Weekly Roundup: Week Ending June 26, 2020

This weekly roundup of health law news includes reporting on recent court decisions,

medical technology advancements related to vaccines, chemotherapy and other areas,

and new initiatives launched by the Department of Justice and the FDA. Read more >>

COVID Lockdowns: Why Didn't They Produce a Greater Reduction in Air Pollution?

Even though we stopped driving, flying and going out during COVID-19 lockdowns, air

pollution did not decrease significantly. Professor Heather Payne examines the reasons

for this and explains why pollution might become worse than the pre-COVID period once

lockdowns are fully lifted. As decreases in air pollution can improve health outcomes,

Professor Payne also suggests areas of focus in decreasing pollution levels. Read more >>

Air Pollution and COVID-19 Mortality Rates

Professor Heather Payne examines the environmental aspects of COVID-19. "We’ve learned

through this crisis that higher levels of air pollution lead to a higher level of

mortality from COVID-19. Specifically, a Harvard study concluded that “a small increase

in long-term exposure to PM2.5 leads to a large increase in the COVID-19 death rate.”

People who lived with long-term pollution exposure for 15-20 years had significantly

higher mortality rates." Read more >>

Health Law Weekly Roundup: Week Ending June 19, 2020

The Center for Health & Pharma Law at Seton Hall has compiled a weekly roundup of

interesting news articles related to health law. This week's summary is focused on

the pharmaceutical industry, the impact of COVID-19 on health and wellness, and medical

device innovations. Read more >>

Ask a Compliance Officer Series: Regina Gore Cavaliere of Esperion discusses COVID-19

Compliance Challenges and Strategies for Re-entry of Field-Based Colleagues

Regina Gore Cavaliere, a long-time member of Seton Hall Law’s U.S. Healthcare Compliance

Certificate Program and Plus Program faculty, is currently the Chief Ethics and Compliance

Officer at Esperion. Seton Hall Law sat down with Regina to talk about emergent risks

and compliance strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Read more >>

Seton Hall's Healthcare Compliance Programs Have Gone Virtual!

The Healthcare Compliance Certificate Program is now offered in a new unique remote-learning

format that will continue to deliver the same content through a blend of thoughtful

expert presentations, case study analyses, offer opportunities to get to know fellow

participants, and earn a Compliance Certificate. Learn more >>

Class Update - COVID-19: Current Topics in Pandemic Law and Policy

In Seton Hall Law’s newest course COVID-19: Current Topics in Pandemic Law and Policy, Prof. Jennifer Oliva’s students spent the first week of class discussing and analyzing

the book Pandemic by Sonia Shah, an award winning science journalist. The book draws

parallels between Cholera and newer pathogens like Ebola, coronaviruses and drug-resistant

superbugs. It emphasizes the cultural, social, and economic commonalities that have

characterized pandemics throughout human history. Read more >>

How the Department of Justice’s “China Initiative” Impacts Industry and Academia

The arrest last month of a former Cleveland Clinic Foundation employee for allegedly

failing to disclose to the National Institutes of Health that he held positions at

universities in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is the latest in a string of

cases under the Department of Justice’s “China Initiative.” Professor Margaret K.

Lewis examines case. Read more >>

Student’s Inspiring Journey to Sobriety Featured on Popular Website

Domenick Scrivanich, Class of ’21, overcame great personal hurdles to arrive at law

school two years ago. Now, sober for 7 years this November, Dom’s future holds hope

and promise. “I came to law school so that I could help addicts and alcoholics,” says

Dom. “I want to use my degree to do some good and hopefully positively affect the

lives of those still sick and suffering in a major way, whether it be through lobbying

or acting as general counsel for a large drug rehabilitation center.” Read more >>

Governor Murphy Nominates Graduate of Seton Hall Law's Pre-Legal Program

Governor Phil Murphy nominated Fabiana Pierre-Louis, a graduate of Seton Hall Law