Nick Reiner appeared in court for his arraignment. (C)REUTERS

When defendants with serious mental illness enter the criminal justice system, constitutional

safeguards are often treated as formalities rather than meaningful limits. The result

is a system that lawfully prosecutes mental illness and consigns treatment to prisons

never designed to provide it.

Rob and Michele Reiner were murdered in their home, apparently by their adult son,

Nick, who has struggled with mental health issues for many years. In my recent conversation

with The New York Times, I discussed the legal path that now lies ahead for Nick, from competency hearings

to trial and a possible insanity plea.

Sadly, Nick Reiner’s case is not an outlier. It is part of a long and troubling pattern involving criminal defendants with serious mental illness. Many Americans remember David Berkowitz, better known as the “Son of Sam,” who killed six people in the 1970s claiming that his neighbor’s dog had told him to do it. Or James Holmes, who killed 12 people when he opened fire in a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, in 2012. Far more cases attract little attention, though the underlying issues are the same.

In cases like these, the criminal justice system is pulled in opposite directions. On one side is accountability and justice for victims. On the other is fairness to people who commit crimes—sometimes horrific ones—while suffering from diminished mental capacity. The law attempts to balance these interests, but the balance is uneasy.

Fairness requires that we not prosecute defendants who cannot understand the charges against them or assist in their own defense. It also means that, in most states, defendants will not be held criminally responsible if they could not understand that their conduct was wrong at the time of the crime.

In practice, however, these standards are modest. Understanding the charges is a low threshold. Defendants may suffer from serious, untreated mental illness, including schizophrenia, and still grasp the nature of the accusations and the basic mechanics of a criminal trial. Even defendants who were floridly psychotic when they committed a crime often understood that killing, stealing or breaking into a home was wrong.

This reality explains why criminal cases against mentally ill defendants routinely move forward—and why insanity pleas almost always fail.

The result is predictable. Mentally ill defendants are tried. They are convicted.

And responsibility for their care shifts not to mental health systems, but to Departments

of Corrections—institutions ill-equipped for treatment and never intended to serve

as the nation’s largest mental health providers. So long as the law permits this transfer

of responsibility, it tolerates a system that stretches criminal process beyond its

constitutional purpose and places correctional institutions in a role the law never

designed them to fulfill.

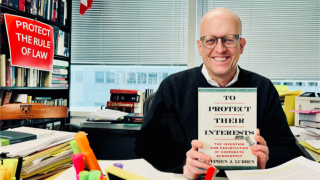

John Kip Cornwell is a professor of law at Seton Hall University School of Law. His scholarship focuses

on the intersection of criminal and mental health laws, with particular attention

to the constitutional limits on states’ authority to address criminal offending linked

to mental disability. An expert in criminal procedure, he is the author of The Glannon Guide to Criminal Procedure.

John Kip Cornwell is a professor of law at Seton Hall University School of Law. His scholarship focuses

on the intersection of criminal and mental health laws, with particular attention

to the constitutional limits on states’ authority to address criminal offending linked

to mental disability. An expert in criminal procedure, he is the author of The Glannon Guide to Criminal Procedure.

For more information, please contact:

Seton Hall Law Office of Communications

973-642-8714

[email protected]