(C)Seton Hall Law Office of Communications.

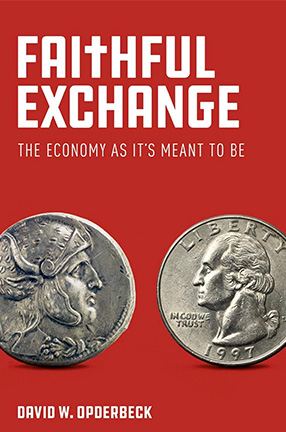

In Faithful Exchange: The Economy as It’s Meant to Be, Professor David Opderbeck argues

that the economy is not an impersonal system but “a story shaped by human choices,”

rooted in law, technology and moral responsibility. Drawing on theology, legal history

and contemporary debates over profit and power, the book calls for recentering human

dignity in how we think about markets and growth.

What if the economy isn’t something that simply happens to us? What if it’s something

we actively create — through law, technology and the choices we normalize? “We tend

to think the economy structures us,” David Opderbeck observes. “But it’s human beings

who structure these relationships for the goods that they decide are the goods that

we want.”

That insight anchors Faithful Exchange: The Economy as It’s Meant to Be (Fortress Press, 2025), a wide-ranging and timely meditation on money, power and moral responsibility in an era of profound economic and technological disruption.

Opderbeck pushes back against the idea that the economy is an impersonal system governed by its own rules. Instead, he presents it as a human endeavor shaped by law and ethical choice. Drawing on his earlier work in law and theology, he explains that property arrangements shape how people relate to one another and that because property itself is created and enforced through law, economic life is never morally neutral. It inevitably reflects what a society chooses to value, reward and tolerate.

Against the backdrop of a consumption-driven economy, Opderbeck argues that this way

of thinking is more urgent than ever. Environmental degradation, social fragmentation

and widespread confusion about money and meaning have intensified as technology accelerates

economic life. “Technology is rapidly evolving to further exacerbate conditions that

are impacting our human economy and human well-being,” he says. In this context, religious

traditions offer not nostalgia but resources for critique and moral clarity.

Against the backdrop of a consumption-driven economy, Opderbeck argues that this way

of thinking is more urgent than ever. Environmental degradation, social fragmentation

and widespread confusion about money and meaning have intensified as technology accelerates

economic life. “Technology is rapidly evolving to further exacerbate conditions that

are impacting our human economy and human well-being,” he says. In this context, religious

traditions offer not nostalgia but resources for critique and moral clarity.

Across Christian, Jewish and Islamic thought, Opderbeck explains, money has always been treated as morally ambivalent. “Money is a powerful influence that can lead us astray,” he notes, capable of distorting desire and fueling conflict. At the same time, these traditions affirm that “abundance is a good thing” and that having food, shelter and even things to enjoy are genuine goods. The challenge lies in living honestly within that tension rather than ignoring it.

One of the book’s most compelling sections revisits how earlier thinkers grappled with profit. “For most of the history of Christian thought, profit was considered problematic, if not sinful,” Opderbeck explains. Under just price theory, sellers were expected to charge prices connected to the real value of what they offered. Profit was acceptable to sustain life, but “the pursuit of excessive profits is unjust.”

Opderbeck does not argue for a return to medieval price controls. Instead, he uses this history to resurface a neglected question: When does profit-taking become excessive? That question, he suggests, still applies today — particularly when profit involves “extracting more than the value that you’ve added,” whether through exploitative lending, market dominance or legal structures that privilege power over fairness.

Technology sharpens these concerns. As a scholar of law and technology, Opderbeck is wary of what he describes as a “hands-off approach” to artificial intelligence and emerging technologies. While often framed as radical innovation, he argues this posture is familiar, tracing back to a Silicon Valley ethos that treats technological development as inevitable. “We always recognize there’s this place where human beings want to give ourselves godlike powers,” he says, invoking the biblical story of the Tower of Babel as a warning against unchecked hubris.

Technology itself, Opderbeck emphasizes, is not the enemy. “It brings us together and heals diseases,” he acknowledges. The danger lies in losing “human-centered control,” forgetting that technologies, like markets, are tools meant to serve people rather than dominate them.

Throughout Faithful Exchange, Opderbeck resists reducing economic debates to modern ideological labels. “The underlying question isn’t capitalism versus socialism,” he argues. “It’s a fundamental question about justice.” Efficiency matters, but it is only one dimension of justice and cannot substitute for moral judgment.

That moral framework, Opderbeck suggests, rests on three shared commitments across religious traditions: “Each individual person is of immeasurable value”; human beings are “created in and for community”; and “the measure of your success is how you treat the poor and the marginalized.” Together, these principles offer a way to evaluate economic systems without flattening complexity or denying trade-offs.

Ultimately, Faithful Exchange is a call to responsibility. Markets do not absolve us of moral choice; they amplify it. By reframing the economy as a human story shaped by law, desire and power, Opderbeck challenges readers to ask not only how the economy works — but whom it serves and at what cost.

Seton Hall University School of Law will host a panel discussion on Faithful Exchange: The Economy as It’s Meant to Be with the author on Feb. 3 at 5:30 p.m. in the Rodino Reading Room at One Newark Center.

Registration is open to the public at law.shu.edu/events/david-opderbeck-book-launch-faithful-exchange.html.

David W. Opderbeck is a professor of law at Seton Hall University School of Law, where he directs the

Program on Faith, Values, and the Rule of Law and co-directs the Gibbons Institute

of Law, Science & Technology, and the Institute for Privacy Protection. His scholarship

explores law and religion, technology law, intellectual property, and the ethical

foundations of economic life. For more information about the book and his other writings,

visit davidopderbeck.com

David W. Opderbeck is a professor of law at Seton Hall University School of Law, where he directs the

Program on Faith, Values, and the Rule of Law and co-directs the Gibbons Institute

of Law, Science & Technology, and the Institute for Privacy Protection. His scholarship

explores law and religion, technology law, intellectual property, and the ethical

foundations of economic life. For more information about the book and his other writings,

visit davidopderbeck.com

For more information, please contact:

Seton Hall Law Office of Communications

973-642-8714

[email protected]