(c)Sean Sime

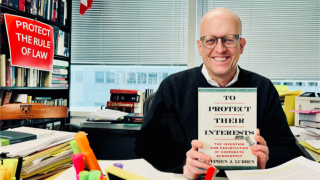

A lifelong reader and legal scholar, Assistant Dean Rochelle D. Edwards reflects on

the books that shaped her and why Black history remains essential reading now.

“I’ve always been an avid reader since I was a kid,” Rochelle D. Edwards recalls reading through library books at a rapid pace as a child, as if reading 10 books every two weeks were the most ordinary thing in the world. Growing up in Indianapolis, Edwards spent her summers haunting public libraries—sometimes in towns where she didn’t even live. “They would still let me check out books because they knew I would bring them back.”

That early love of reading eventually became a vocation. Today, Edwards is assistant dean for Equity, Justice and Engagement and a PhD candidate whose scholarly life revolves around history, law and race. “Being a graduate student, being a scholar, really gives me the benefit of reading books for a living,” she says. “It’s the best job ever.”

The reading list Edwards shared for Black History Month was born out of urgency as a response to a national moment. After the murder of George Floyd, parents and students kept asking the same question: Why are Black people so angry? Her response was simple. “Maybe you should read some of these books,” she told them, offering historical context, legal grounding, and practical understanding all at once.

“I was really trying to help parents and students understand what had happened historically in this country,” she explains, “and also provide them with some resources” for talking about race, protest and civil rights.

Edwards organized the reading list the way her mind works—by historical period. One of the foundational texts she highlights is A. Leon Higginbotham’s In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process, which she calls essential for anyone studying race and law. “It’s really the first piece of scholarly work that dives into the history of race and the law in America.”

Another core text is Peter Wood’s Black Majority, a book deeply connected to her own dissertation research. “When he says Black majority, he literally means that at some point in South Carolina, there were more African slaves than white men living in the state,” she notes. That reality, Edwards explains, shaped the laws and social structure of the region.

Another cornerstone is Theodore Allen’s The Invention of the White Race, which examines how slavery became racialized in colonial Virginia, particularly after Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676. “That’s the period of time where we see when some groups of white people—upper-class white people—are trying to demonstrate to lower-class whites that there is a difference between them and Africans who had been enslaved.” Race, she explains, was used deliberately as “the tool to create that divide.”

She frequently references historian Barbara J. Fields, whose work frames white supremacy as a political strategy rather than an inherent belief. “Fields reminds us that ‘White supremacy is a slogan, not a belief’,” Edwards emphasizes. “It was purposely used by wealthy whites to prevent people who had everything in common from joining together.”

Her list moves steadily through slavery, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, the Civil Rights Movement, and into the present. Many of the books are not new, Edwards acknowledges, but they remain relevant. Of Cornel West’s Race Matters, she says, “This book still matters because race still matters in the United States.”

She also emphasizes the importance of centering Black women’s experiences, particularly through Dorothy Roberts’ Killing the Black Body. “It’s not a new text but it still speaks directly to what’s happening right now,” especially around reproductive rights and Black maternal health.

Black History Month at 100: Reading List

Despite the weight of these topics, Edwards keeps returning to why reading matters now. “We’re just flat out being lied to every day,” she says plainly. “History is trying to be erased. Books are being banned, and people are being told things have never been this bad before. That’s just not true.”

For students, particularly those in law school questioning their path, Edwards believes books can reignite purpose. “If they need something to get that fire burning again,” she says, “a lot of these books will do that.”

Black History Month, in Edwards’s view, isn’t about looking backward. It’s about understanding where we are—and deciding where we’re willing to go next.

Working closely with student affinity organizations, Edwards is also leading the Diversity Banquet, an event celebrating diversity and inclusion in the legal profession. This year’s program on March 23 includes a networking reception and a keynote address by the Honorable Zahid Quraishi, U.S. District Court Judge for the District of New Jersey. For details and registration, visit Diversity Banquet.

For more information, please contact:

Office of Communications and Marketing

(973) 642-8714

[email protected]